- Home

- Jeremy C. Shipp

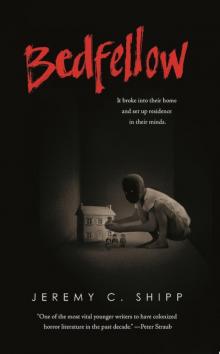

Bedfellow

Bedfellow Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author's copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my family

FRIDAY

Hendrick

Hendrick prides himself on always responding well to an emergency, but he freezes in place when a man in a Space Jam nightshirt crawls through their living room window. The intruder carries a tattered grocery bag, which leaks a bright green ooze onto the hardwood floor. These floors are only two years old, Hendrick wants to tell the man, but of course he doesn’t.

Instead, he says, “Go upstairs.”

The man in the nightshirt tilts his head to the side, as if wondering why he should go upstairs at a time like this. But obviously Hendrick is speaking to his wife, who’s sitting on the leather couch behind him. He can feel her fear emanating against his back, the same way he can sense her displeasure at a crowded office party.

“Imani, go,” he says.

To be quite honest, Hendrick has often fantasized about a moment like this. On a date with his wife, Hendrick will imagine a man with a semiautomatic charging into the movie theater. In his mind, Hendrick will crawl through the aisle and lunge forward and burrow his thumbs into the terrorist’s eyes.

In the here and now, Hendrick doesn’t lunge forward. But he does take a step and point a threatening finger at the man’s grimy face.

“Get the fuck out of my house,” Hendrick says, proud of the line. He’s feeling bolder by the second, because this Space Jam guy is obviously some poor, unarmed bastard who probably thinks he’s in Narnia right now. Hendrick grew up in San Diego, and there he learned that homeless people are almost always harmless. He recalls a friend of his throwing an empty Dr Pepper can at an old man in a bright pink robe, and the old man only whispered and turned away.

“Listen, buddy,” Hendrick says, sounding a little too much like his father for his taste. “I don’t want to call the police if I don’t have to.” In truth, he’s already thinking about tonight’s news report, where he’s standing, slightly dazed in front of his house, the red and blue lights flashing on his face. Rosalita Little will come at him with her oversized microphone and say, “What inspired you to confront the intruder yourself, Mr. Lund?”

The nightshirt man responds to Hendrick’s threat by smiling a little.

“Do you have Howard the Duck on Blu-ray?” the man says, swinging his grocery bag gently from side to side. He speaks in a melodious, high-pitched voice that Hendrick finds offensive. “I heard there’s a naked duck woman with boobs in that movie. Have you seen it?”

“I’m calling the police,” Hendrick says, his Android already in his hand. “This is your last chance to get the fuck out of here.”

“A DVD would be fine too, if you don’t have a Blu-ray.” The strange man sprays a line of green goo all over the floor with his damn swinging.

While Hendrick dials 911, the nightshirt man opens his grocery bag and stares inside with almost pupil-less eyes. What kind of drug does that to a person’s eyes?

“Nine-one-one,” the dispatcher says. “What’s your emergency?”

Hendrick opens his mouth but his words catch in his throat like a craggy chunk of ice he accidentally swallowed. For one ridiculous moment, he considers asking the dispatcher why a duck would even have boobs when they’re not mammals. This is a common enough occurrence for Hendrick, whose thoughts often veer left during somber situations like funerals or project meetings or arguments with his wife. He’ll often burst into laughter and embarrass himself. He makes sure not to laugh now.

“Nine-one-one,” the dispatcher says again.

“I think my bag is leaking,” the homeless man says.

In an attempt at an even tone, Hendrick explains the situation and gives his address. He gives his address a second time, just in case.

Hendrick doesn’t go upstairs and lock himself in a room with his family, as the dispatcher suggests. He strolls over to the fireplace and picks up the glass Coke bottle that someone (probably Kennedy) left on the mantelpiece. The girl never does pick up after herself.

The Space Jam guy studies Hendrick with his tiny eyes. “I’ve heard that Mexican Coke is better than the regular kind. Is that true?”

Hendrick stands at the bottom of the stairs, with his arms crossed over his chest. He waits. He can feel a rivulet of sweat trickling down his back, and part of him wishes for an end to all this. The other part isn’t quite done yet.

Kennedy

As a small child, Kennedy would navigate the world as an intrepid explorer, climbing cabinets and squeezing between fence posts and disappearing into clothing racks at the mall. Now, at thirteen years old, she still feels that whirling, staticky energy inside her. She sits on the bathroom tile, wriggling each of her toes, wanting to race downstairs to her dad.

“Has he texted you back yet?” Kennedy says.

“Not yet,” her mom says, standing right next to the bathroom door. “I’m sure he’s fine. The police will be here soon.”

Her mother called the police hours (or was it minutes?) ago. Kennedy knows that some guy came into their house, but what disturbs her most is how quiet and still her house has become. She expected yelling, screaming, struggling. Instead, she can’t hear anything from downstairs. Her mom and brother are hardly moving. Even the wind outside seems to have died down since they locked themselves in here. The girl realizes her thoughts are running rampant in her head, and she’s being ridiculous, but the silence of her home still disquiets her.

Sitting beside her, Tomas hands her an ant in a top hat drawn on his yellow notepad. Drawing Battle often begins with an insect or a mouse. Kennedy takes the ballpoint pen and starts sketching an anthropomorphic shoe that could smash the ant. Next, Tomas will draw a ball of flame or any object or creature that could destroy the shoe, and the game will go on from there. Kennedy doesn’t consider herself much of an artist, and her turns tend to last a minute or less. Tomas, on the other hand, will strain himself to create a moon with craters for eyes and mountain ranges for lips. He’ll spawn a giant robotic jerboa crushing New York City. He’ll always end the game by drawing God, who, depending on the day, will turn out to be a Gandalf-looking wizard or a hippo vomiting a swirling galaxy.

After Kennedy finishes her cross-eyed shoe, she stands and cracks her knuckles.

“Can you not?” her mother says, still tapping at her phone.

Kennedy is bewildered by the fact that her mother could worry about knuckle-cracking at a time like this, but her mother often surprises her in this way.

“Has he texted yet?” the teenager says.

“No,” her mother says, with a small quiver in her voice. “I’ll let you know when he does.”

At the sound of the small quiver, the static inside Kennedy whirls faster. She imagines her father lying on the hardwood floor downstairs, being silently strangled by a man in a black ski mask. Kennedy sidesteps her brother and slowly reaches out to touch the brass handle of the bathroom door.

Before her mother notices what’s happening, Kennedy scrambles outside and surges down the hallway. Eventually, she slows and turns her head.

From here, Kennedy can see her father sitting mo

tionless at the bottom of the stairs. The man who broke in isn’t wearing a ski mask after all. He’s sitting cross-legged on the floor, wearing a Bugs Bunny shirt.

The man glances up at Kennedy and gives a little wave.

Her dad stands and turns around.

“Go to your mom,” he says, and he sounds calm. He looks a bit sweaty but Kennedy can’t see any cuts or bruises.

When someone grabs her arm, Kennedy half expects another man in a matching Bugs Bunny shirt to be standing beside her. But it’s only her mother.

Her mother mouths a couple words that Kennedy doesn’t catch and pulls her back down the hall. Twisting away, the teenager slips into Tomas’s bedroom. She heads straight for the closet, where she finds her brother’s stubby aluminum bat.

This time, when her mother leads her back to the bathroom, she follows.

“What were you thinking?” her mother whispers, still holding her arm with a hand like a metal claw.

Kennedy wriggles herself free. “Dad’s okay, I think. The guy who broke in was just sitting there.”

Her mother continues to stand beside her, obviously on guard in case her daughter tries to make a run for it again. Kennedy glances at her brother and notices that he’s staring at the bat in her hand.

“Just in case,” she says.

Her brother shifts his gaze to his notepad. He dangles his pen over the paper without drawing anything.

“Did the man have a gun?” her mother says, quietly.

“I didn’t see one,” the teenager says.

The three of them sit in silence for a while, and the cypress stands motionless outside the high bathroom window.

Kennedy thinks about the unwashed man on the floor, and about her father’s tirades whenever he spots someone giving money to a homeless person. He’ll only get worse after tonight. He’ll say, “Great, give that guy some drug money so he can tweak out and break into our house like the last guy.” Kennedy almost wishes the man on the floor were a well-groomed thief with a mustache, like in an old British film.

“Give me the bat, honey,” her mother says.

Kennedy studies her mother for a moment, and then hands over the squat little weapon. Her mother rests the bat across her lap. She taps at her violet, furry phone.

Tomas hands over his notepad, and Kennedy wonders who could defeat this shoe-eating ninja goat? A tyrannosaurus samurai? The teenager scribbles on the next blank piece of paper. When she stretches out her legs and wiggles her toes, the wind picks up again. The cypress sways in the tiny window above. She thought the movement would make her feel less uneasy, would make the whirling static lull a little in her limbs, but she was wrong.

Imani

With a sense of dread, Imani scrolls backward in time through the digital albums on her phone. Her crow’s feet vanish, and her children shrink smaller and smaller until they disappear altogether. Her husband’s gray hairs become imbued with the color of the sequoia trees she would jokingly hug during their camping trips. “I’m a tree hugger,” she would say, every time. As she rewinds their lives together, Hendrick also appears increasingly happy. More often, he grins with his whole face and he gives his stupid double thumbs-up to the camera. Imani slows down at a picture of the two of them standing in front of a dark green pond, a duckling balanced on Hendrick’s palm. She told him not to pick up the duck, but he did anyway.

But none of this is the point of Imani’s search. When the man in the nightshirt first appeared, standing behind the open bay window, he winked at her, knowingly. And she recognized him.

Imani scrolls through the albums with a trembling thumb, but she can’t find the man anywhere. She’s afraid that he knew her during her wilder days, back when she didn’t take many pictures. Did she wrong him somehow? For so many years, Imani has pretended to be a nice, normal mother and a nice, normal wife. Of course a man would crawl out of the past to punish her for this charade.

Imani attempts to jostle these thoughts out of her with a shake of her head. She’s being silly. The man downstairs is no one, and she didn’t even get a good look at his face, anyway. How could she recognize him at all?

She continues to search through her photos until Hendrick finally texts back with, Everything’s fine.

For a second, she strokes the furry phone with googly eyes, as if in thanks for the good news.

“Your dad says everything’s okay,” Imani says, standing from the closed toilet. “I’m going to check and see what’s happening. You two stay here and lock the door behind me.”

“Can’t I come with you?” her daughter says, already standing.

“I cannot toilet you do that,” the mother says, because she wants her home to feel normal and stupid again.

The girl presses her hands against the sides of her face. “That was horrible.”

Imani shrugs. “Stay here.”

She leaves, almost tripping as she steps over her son’s legs, and she takes the baseball bat with her. Thankfully, she hears the soft click of the lock behind her.

On her more stressful days, Imani will sometimes drive over a bump in the road with her Flux, and she’ll have to look back to make sure she didn’t hit a raccoon or a cat or a human being who happened to be lying flat on the street in the dark. And if she doesn’t look back, she’ll picture a half-dead possum dangling under her car, his flesh scraping against the road, until she can get home and check. Tonight, while she makes her way through the hall, she pictures a man leaping out from one of the bedrooms. And after she swings wildly with the bat, she realizes too late that she’s smashed Hendrick in the face, his nose gnarled, his teeth tumbling down a waterfall of blood. She attempts to quiet her imagination with a few deep breaths.

From the stairs, she can hear guttural whispers coming from the living room, but when she makes her way down, she realizes what she’s hearing is the crackling of a fireplace on the TV. Her husband loves the sound of fire, and he’ll often play one of these damn videos while reading or playing one of his silly phone games.

“Hendrick?” she says, pausing at the bottom of the stairs.

“Everything’s fine,” he says, echoing his text.

She finds her husband with his bare feet on their oversized ottoman, as if a man didn’t invade their home only minutes ago. He’s caressing an Old Fashioned ornamented with a maraschino cherry and an orange wheel. He only adds the fruit during special occasions. Imani despises Old Fashioneds with a passion, so she assumes the second cocktail on the serving tray isn’t meant for her.

“What happened?” Imani says.

Her husband taps at the side of his glass with an index finger and gives a sheepish-looking smile. “It was all a stupid misunderstanding.” He turns down the sound of the fire slightly with the remote. “Marvin tried ringing the doorbell, but it’s not working, apparently. So, then he tried knocking, but we couldn’t hear him over the TV. That’s why he came over to tap on the window.”

Imani does like to up the volume of the TV to nearly earth-shattering levels. She remembers the man at the window tapping on the glass, and she remembers screaming. She remembers saying, “What the fuck is that? What the fuck is that?”

Hendrick shakes his head and sighs. “You screamed and I went into full papa bear mode. I still can’t believe I called the police. Fuck. They came to the door, and I had to explain everything. Marvin’s still shaken up.”

At this point, Imani glances around the room for this so-called Marvin, half expecting him to be crouching in a corner, watching all of this unfold. The name Marvin sounds very familiar somehow, and the wife is even more convinced that he’s some weirdo from her past.

“He was trying to come inside,” Imani says, the artificial fire still sputtering at her back.

Hendrick shakes his head and then takes another sip of his drink. A bit of the liquid spills onto his T-shirt. “He tapped on the window and you screamed because we were watching that fucking serial killer show. You know how you get.”

Imani remember

s Marvin standing at the window, tapping at the glass. She thought he winked at her, but it could have been a blink. He could have been tapping and blinking and nothing more.

When Marvin strolls out of the downstairs bathroom, Imani feels a sudden urge to bash his head in with the bat or run outside, or one and then the other. The feeling almost instantly collapses, however. His clean-cut look comes as a relief to her, with his excessively gelled side-part and his collared button-up patterned with blurry white stars. She doesn’t know exactly what she was expecting to see when he stepped out of the bathroom, but this is not it.

“Hey there,” he says, and he takes a seat next to Hendrick. He puts his feet up on the ottoman, right next to her husband’s. “You have a beautiful home. The layout kind of reminds me of the house from Troll. Have you seen it?”

“No,” Imani says.

“It’s no Troll 2 but it’s pretty good.” Marvin takes a sip of his cocktail, and judging by his expression, he enjoys Old Fashioneds as much as Imani does. “You know what’s weird? In Troll, the main character is a little boy named Harry Potter who ends up doing magic. No one ever believes me when I say that, but it’s true.”

By now, Imani’s feeling like a complete idiot, because she’s finally remembered where she knows this guy. He’s the man who gave Tomas the Heimlich earlier that day. When Tomas started choking, Marvin seemed to appear out of nowhere, softly lit in the dim steakhouse. He wore the same dark dress pants and starfield shirt. Imani was so focused on Tomas that she hardly looked at the man who saved him. She thanked him, again and again, but she kept her eyes on her son.

Marvin is here, of course, because Hendrick must have invited him over for a drink. Hendrick will often invite work friends over without telling Imani, which annoys the hell out of her when she’s not in the mood to entertain.

“Thank you for what you did,” Imani says. “You really saved the day.”

“I guess I’m a regular Mighty Mouse,” Marvin says, pushing the cocktail away from himself a little with a single finger.

Vacation

Vacation Cursed

Cursed Bedfellow

Bedfellow The Atrocities

The Atrocities Sheep and Wolves

Sheep and Wolves